Hello everyone how are you doing? Today’s theme is “Kabuki” which was recognized by UNESCO as an intangible cultural heritage in 2008, along with “Bunraku“,and “Noh/Nohgaku” that are classic “Cool Japan” traditional performing arts.

Contents

What are Japanese traditional performing arts?

As I mentioned the three classical performance arts listed on UNESCO, they are “Noh/Nohgaku“(Noh play,drama or Noh farce), “Bunraku” (Japanese doll-puppet theater), and “Kabuki“.

Frankly speaking, however, it’s difficult for even the Japanese to explain how three differences are if we haven’t seen them in theatre.

These are dramas born from the lives of ordinary people, so the content is trivial, such as tragedies, comedies, romances, small quarrels, and the like.

That’s because they are apparently quite similar, at first glance, to their performance on stage except masks on their face for Noh and Bunraku doll-puppet for Bunraku.

Here’s an outline of the three as follows,

★ Noh is a play based on classics using masks (The name of Predecessor “Sarugaku” has also been changed to “Noh” by combining Noh and “Kyogen” which was a comedy play/drama characterized by/featuring comical movements)

★ Bunraku is a play using Bunraku dolls (we talk it later)

★ Kabuki is entertainment for the masses

What’s Kabuki

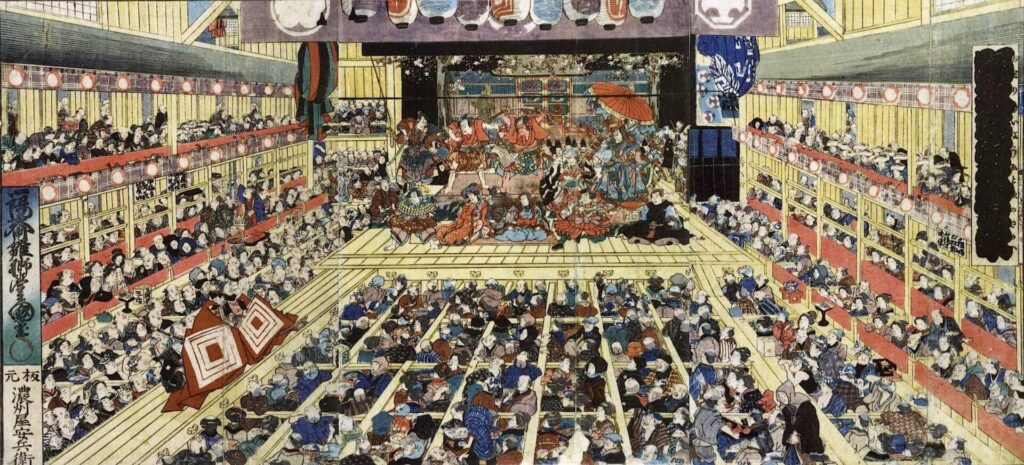

One of the three major classical theaters of Japan, together with the NO and the BUNRAKU puppet theater. Kabuki began in the early 17th century as a kind of variety show performed by troupes of itinerant entertainers.

By the Genroku era (1688-1704), it had achieved its first flowering as a mature theater, and it continued, through much of the Edo period (1600-1868), to be the most popular form of stage entertainment.

Kabuki reached its artistic pinnacle with the brilliant plays of Tsuruya Namboku Ⅳ and Kawatake Mokuami (1816-1893). Through a magnificent blend of playing, dance, and music, kabuki today offers an extraordinary spectacle combining form, color, and sound and is recognized as one of the world’s great theatrical traditions.

Origin of Kabuki

The creation of kabuki is ascribed to Okuni, a female attendant at the Izumo Shrine, who, documents record, led her company of mostly women in a light theatrical performance featuring dancing and comic sketches on the dry bed of the river Kamogawa in Kyoto in 1603.

Her troupe gained nationwide recognition and her dramas became identified as “kabuki“, a term connoting its “out-of-the-ordinary” and “shocking” character.

The strong attraction of onnna (women’s) kabuki, which Okuni had popularized, was largely due to its sensual dances and erotic scenes. Because fights frequently broke out among the spectators over these entertainers, who also practice prostitution, in 1629 the Tokugawa sougunate (1603-1867) banned women from appearing in kabuki performances.

Thereafter, wakashu (young men’s) kabuki achieved a striking success, but, as in the case of onna kabuki, the authorities strongly disapproved of the shows, which continued to be the cause of public disturbances because the adolescent actors also sold their favors.

Edo-Period Kabuki

In 1652 wakashu kabuki was forbidden, and the shougunate required that kabuki perfomances undergo a basic reform to be allowed to continue.

The performers of yaro (men’s) kabuki, who now began to replace the younger males, were compelled to shave off their forelocks, as was the custom at the time for men, to signify that they had come of age.

They also had to make representations to the authoritiies that their performances did not rely on the provocative display of their bodies and that they were serious artists who would not engage in prostitution. By the mid-17th century, the major cities, Kyoto, Osaka, and Edo, were permitted to build permanent kabuki playhouses.

By the beginning of the Genroku era in 1688 there had developed three distinct types of kabuki performance: jidai–mono (historical plays) , often with elaborate sets and a large cast: sewa-mono (domestic plays), which generally portrayed the lives of the townspeople and which, in comparison to jidai-mono, were presented in a realistic manner: and shosagoto (dance pieces), consisiting of dance performances and pantomine.

In the Kyoto-Osaka area, Sakata TojuroⅠ (1647-1709), whose realistic style of acting was called wagoto, was enormously popular for his portrayal of romantic young men, and his contemporary Yoshizawqa Ayame (1673-1729)consolidated the role of the onnagata (female impersonator) and established its importance in the kabuki tradition.

For a period of some 10 years until about 1703, when he returned to the puppet theater, Chikamatusu Monzaemon (1653-1724) wrote a number of kabuki plays, many of them for Tojuro Ⅰ, which gained public recognitiion for the craft of the playwright.

The commanding stage presence and powerfu acting of Ichikawa DanjuroⅠmade him the premier kabuki performer in Edo, and as a playwright, under the name Mimasuya Hyogo, he was once considered the rival of the great Chikamatusu.

Modern Kabuki

After the Meiji Restoration actors such as Ichikawa DanjuroⅨ(1838-1903) and Onoue KikugoroⅤ(1844-1903) urged the preservation of classical kabuki, and in the later years of their careers agitated for the continued staging of the great plays of the kabuki tradition and trained a younger generation of actors in the art that they would inherit.

In the postwar era the popularity of kabuki has been maintained and the great plays of the Edo period, as well as a number of the modern classics, continue to be performed in Tokyo at the Kabukiza and the Natonal Theater.

However, offerings have become considerably shortened and, particularly at the Kabukiza, limited for the most part to favorite acts and scenes presented together with a dance piece. The National Theater continues to present full- length plays.

The average length of a kabuki performance is about five hours, including intermissions. The roles once played by the great postwar actors like Ichikawa Danjuro ⅩⅠ(1946~), Matsumoto Koshiro ⅠⅩ(1942~), Onoue Kikugoro (1942~), Bando Tamasaburo (1950~), Kataoka Takao (1944~), and Nakamura Kankuro Ⅴ(1955~). Dramas in which Tamasaburo Ⅴappears in the role of the onnagata and Nizaemon ⅩⅤ that of the leading man are always well attended.

The Kabuki Stage

The kabuki stage uses a draw curtain. It has broad black, green, and orange vertical stripes and is normally drawn open from stage right to stage left accompanied by the striking of wooden clappers. The curtain may also serve as a backdrop for brief scenes given before or after the performance on the main part of the stage.

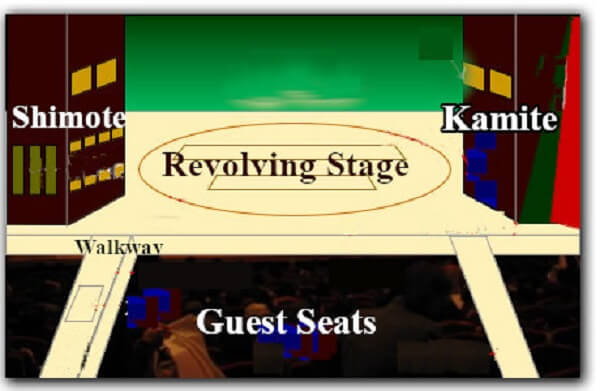

Kamite(stage left) is regarded as the place of honor and is occupied by the characters of high rank, guests, and important messengers or official representatives.

Shimote(stage right) is occupied by characters of low rank and members of a household, most entrances and exits take place on this side, usually by way of the hanamichi. A unique feature of the kabuki stage is the circular platform that can be rotated to permit a second scene to be performed simultaneousely with the scene already in progress or to dramatize a flashback.

Acting forms

The powerful influence of a long theatrical tradition is graphicaly illustrated by kata(forms), the stylized gestures and movements of kabuki performers. Since kata are not subject to rejection at the whim of the actor, they have helped to maintain the artistic integrity of kabuki.

Tate(stylized fighting), rappo(dramatic exit accopmanied by exaggerated gestures), mie(striking attitude), and dammari(silent scene) all belong to this category.

Costume

Costume, wig, and makeup are carefully matched with the nature of a role. In general, the costumes in jidai-mono are more stylized and elegant, befitting members of the nobility and the samurai class.

By contrast, the prevailing fashions of society during the Edo period are portrayed quite realistically in sewamono plays. The costumes used in shosagoto dance pieces are especially noted for their color, design, and workmanship.

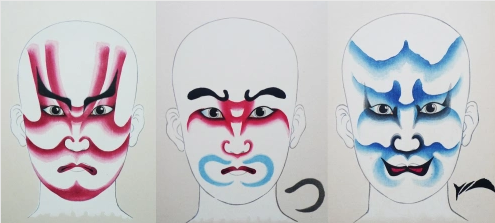

Wigs are classified according to age of characters, historical period, social status, occupaton, and other considerations. Makeup varies widely depending on the role. The most striking example is kumadori, an established set of masklike makeup styles numbering about 100 and used in jidai-mono. Here’s some examples of kumadori makeup.

Shuumei (Stage Names)

Each performer belongs to an acting family by whose name he is known. Professionally, he is part of a closely knit hierarchical organization, headed by one of the leading actors, and must spend many years as an apprentice. An actor may eventually receive a new name (shuumei) as a mark of his elevation to a higher position withing the professional organization.

It is awarded at a shuumei ceremony and in the company off his colleagues the actor delivers from the stage an address in which he requests the continued patronage of the audience.

The name Ichikawa Danjuro, which can be traced back to the formative years of kabuki, is regarded even today as the most illustrious of honors a kabuki actor can receive.

Ichikawa Danjuro XII (1946-2013) right in the above photo and left is his son, Ichikawa Ebizo (1977-)

Finally, it is performed daily at the Kabukiza (above photo)in Higashi-Ginza regardless of the day of the week from the 1st to the 25th of every month. Let’s enjoy the unique world view and charm of Japan’s traditional performing arts・kabuki.

Leave a Comment